by Rachel Abbott

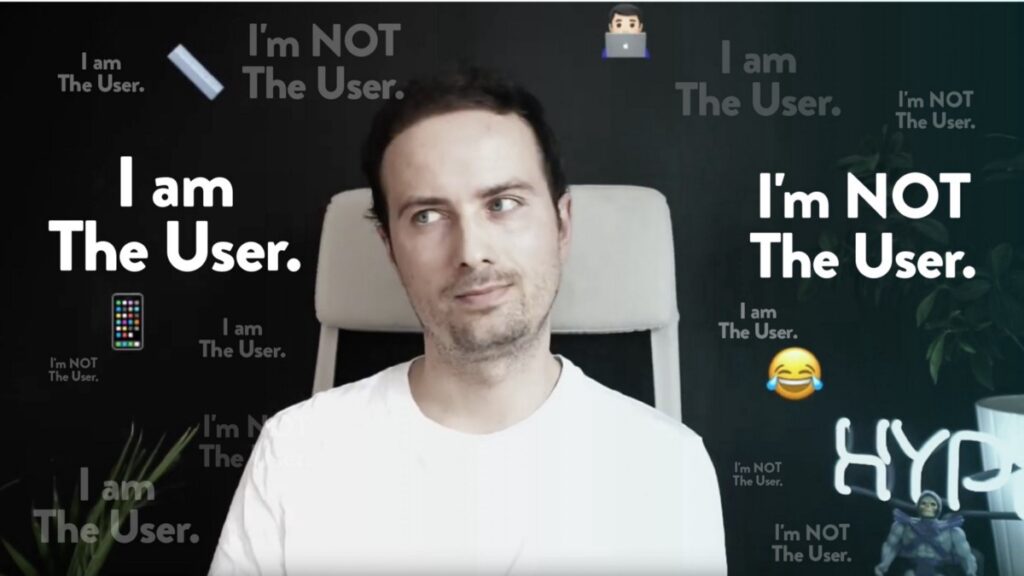

If you work in UX or UCD, you have probably heard Jakob Nielsen’s statement that “One of usability’s most hard-earned lessons is that ‘you are not the user.’”— it’s become almost a mantra — and for a good reason.

As researchers, designers, developers and so on, we have to constantly be aware of projecting our own thoughts, feelings, expectations and biases onto our services and products. We cannot hastily make assumptions or expect our end users to behave as we would. We can’t evaluate the usability or potential success of a product based on how we find ourselves reacting to it. This is known as the ‘false consensus effect”.

The false consensus effect refers to people’s tendency to assume that others share their beliefs and will behave similarly in a given context. Anyone who disagrees must be much different. We are wise then, to be aware of this bias and to ensure that we are using evidence-based research methods to learn about our users, involve them in the design process, and interact with them.

But what happens when you are the user?

More often than not, we work on designing services for people we are very separate and distinct from. They have needs we don’t, services and systems they use that we will never touch. They are not me. I’ve researched with teachers, 5-year-olds, HR managers, care workers, GP’s. I have truly not shared their experiences or the context in which they operate — research is the way to understand that. But recently, I’ve been reflecting on how it feels when we ARE a user of the service we are working on. This will probably be more common if you work on national central government services that cover things such as travel, benefits, childcare, education, taxes etc.

I’ve recently spent almost 2 years on NHS Digital’s Covid19 testing services, researching with hundreds of participants. During this time, I have also been a user of those services I worked on — ordering lateral flow test kits, reporting my test results, booking a PCR test at a walk-in site. I have been both a researcher and a user.

I will admit I felt very excited and proud to use the service I had helped to design through my research (I used to tell friends and family ‘I helped make this!’) and it was fascinating to see it ‘in real life’ from the eyes of the people I’d spoken to. However, I also experienced the frustrations that users described to me in interviews — even though I often knew why things were occurring (policy, time constraints, dev capacity, service design dependencies) — you cannot always shake that initial head shake moment.

I asked some of my colleagues if they had had similar experiences and how they made them feel.

“I actually found it even more annoying when others in the same team, also using the service, extrapolated their experience of one to all users when I was working very hard not to!”

“the UR felt extra relatable — beyond the usual empathetic UCD designer mindset”

“Back in my older days I worked on an internal system for staff that I also used as a staff member. I’d been chosen to work on it because I was an SME on the benefit but that meant I ended up suggesting and implementing changes that support my SME knowledge rather than the general knowledge of the audience”

“I’ve used NHS login both when I worked on it and most recently when I helped my dad through it to get his COVID pass. My dad was very confused why he had to also upload a video of himself rather than just uploading his ID which seems very normal process”

“I think that sometimes the more you can relate to something the harder it is not to think you “know” what should be done, its human nature…”

So it seems that the experience is a mixed bag — it can help you empathise more deeply, pick up on pain points and really understand the wider user experience, but it can also pose a risk of over-investment in outcomes or seeking to make changes based on your own specific experience rather than wider evidence.

Here are some tips for balancing this if you find yourself in the position of being one of your users:

- Be conscious of your biases on a frequent basis — you can try to remove some element of bias by bringing in additional/different people to note take and analyse research findings so you don’t get tunnel vision

- Try to approach the project with ‘fresh eyes’ so as not to project your own assumptions and experiences into design thinking — if you find yourself using a lot of “I” statements, it might be time to take a step back

- Focus on evidence — your experiences can function as a springboard for discussions but iterations should be strongly tied back to larger sets of data and research insights

Thanks to Karen, Joshua, Mike and Mercedes for sharing their experiences with me.