When I was in secondary school, my career plan was to be an Archaeologist. I was really into Time Team and similar documentaries, fascinated by the idea that you could be the first person to set eyes on something in thousands of years. I ended up going a different way in life, but my interest has continued.

I’ve recently been reading a book by Rebecca Wragg Sykes called “Kindred”, which examines the “life, love, death and art” of our Neanderthal predecessors. An evidence-rich analysis looks at everything from lithic (rock tools) production, how animals were hunted and eaten, how they moved through the terrain based on season and weather, to how they used fire and other natural resources.

Another thing that strikes you in this book is an appreciation for the absolute tenacity, attention to detail, patience and skills of those working in Archaeological and Palaeolithic research who often have no more than tiny fragments of rock and bone that help them to create a picture of these early people. I started to consider some of the methodological activities mentioned as metaphors for things we experience in research, particularly user research.

Thinking about UX with an archaeological cap on isn’t necessarily a new thing. There are several blogs on the idea, this one being from UX Planet.

‘Excavating’ to uncover a shared understanding of human behaviour is common to both Anthropology and User Research.

However, I want to share a few of my own observations, specifically linked to things I learned from Wragg Syke’s book.

A story in layers

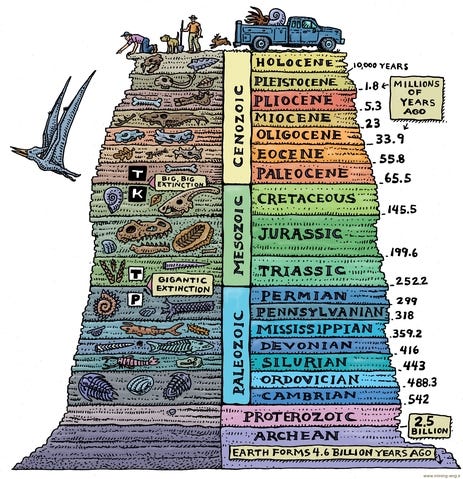

Stratigraphy is a branch of geology concerned with the study of rock layers. The different layers and their location, make-up, specific sediments and inclusions give a literal timeline of what happened layer by layer. You can see when the climate changed when there was a flood when animals inhabited the area, and when species died off.

Wragg Sykes talks about how by examining the stratigraphy of rock caves, the presence of soot and burnt plant material in certain layers of the cave rock, indicates when it was inhabited by Neanderthals, and over a period of time, how frequently it was inhabited.

In UX research, we try to understand the different layers of evidence we have. Every time we add a new design change or product feature, we create a new layer on top of the previous body of research. Often when we join a new product team, there will be layers and layers of previous research to sift through and understand what came before. Each layer of research adds to our understanding and helps create a narrative.

As Michael Wellend (a professional geologist from London) described “[it is] taking pieces of the puzzle and putting them together, connecting layers and piles of layers in a way that makes sense, that tells a coherent story”.

Identify the relationships

Archaeologists are often dealing with large areas of ground in multiple carefully scraped away layers, and as Wragg Sykes points out “the average dig produces tens or hundreds of thousands of carefully collected objects that must be washed, labelled and nestled in individually sealed bags”.

Artefacts also are not often neatly grouped and arranged in a way that makes sense — the shifting of ground, sediment erosion, flood, weather, and time can all cause previously distributed items to merge together into a single mass. This can make it particularly difficult to understand: Which items are connected? Are they from the same time? Used by the same person? What is significant and what might even be a ‘red herring’?

In User Research, we often uncover insights and findings in a messy way. We don’t always know what is relevant or important until we start to compare our findings across different participants and multiple studies and methodologies. Something that initially seems irrelevant can take on new meaning when we analyse it alongside other evidence.

Challenge Assumptions

In the 1880s Scandinavian archaeologists unearthed a grave containing a skeleton accompanied by all the implements required for battle, including shields, an axe, a spear, a sword, and a bow with a set of heavy arrows, along with two horses, a mare and a stallion. A set of game pieces lead researchers to believe that this person was interested in strategy, and may have used the pieces to plan battle tactics. It was the grave of a Viking warrior and naturally was assumed to be a male.

However, in 2017, DNA testing finally revealed the skeleton was actually that of a female.

This is a prime example of where assumptions (in this case about gender roles) meant that for over a century, the wrong conclusion was drawn, furthering the erasure of female warriors from our historical understanding.

In Wragg Syke’s book, she talks about how Neanderthals have suffered from a ‘PR image’ issue — being long assumed and depicted as rag-cladded, stupid, slow, carnivorous brutes. What she shows through a multitude of archaeological evidence is that they were anything but — they finely crafted tools based on need and available resources, they were inventive and adaptable, altruistic, and their diets more varied.

You leave your assumptions unchallenged at your own risk.

Understand the context of use

One of the things that archaeology and its fellow historical disciplines aim to do is to understand what artefacts and sites actually tell us about the people. On the surface, a piece of pottery is just a piece of pottery. But researchers have questions: How was it used? When was it used? What function did it have? Who used it? What does it tell us about them? What can we learn?

A dig site at Schöningen, Germany showed that 75% of bone tools were created from bones on the horse’s left side. This is thought to be because the shape of left side bones provides better grip and gestures for right-handers, but it is clear this is an intentional design choice than a sheer coincidence.

Wear marks on the teeth of Neanderthal children skeletons show different wear patterns to adults — showing that at a certain age they were involved in softening animal hides by chewing, but not yet doing activities like chewing bones or using their teeth in the production of lithics. This shows how children were introduced to adult tasks in an age-appropriate way.

Location of animal bones and butchery marks tell a story of how during certain seasons or climates, certain body parts were eaten ‘on the go’, or brought back to the shelter for further preparation. The story is different with each change in setting.

Understanding your user’s context is important — it helps build the story of the ‘why’ and the ‘how’ and not just the ‘what’.

In Summary:

- Build your story in layers

- Identify the relationships

- Challenge assumptions

- Understand the context of the use

I hope you enjoy your next UX excavation!